FREC 3 & Confined Space Rescue: Casualty Care in Practice

Confined space rescue is often discussed in terms of access, equipment and technical skills. Ropes, winches, tripods, breathing apparatus. All of that matters, and without it, rescue does not happen.

But when things go wrong in a confined space, it is very often the casualty, not the space itself, that becomes the defining problem.

People rarely enter confined spaces expecting to be rescued. Incidents are usually the result of deterioration, exposure, collapse or a sudden traumatic or physiological event. By the time a rescue team is mobilised, the situation has already moved beyond routine.

That is where casualty care stops being a background consideration and becomes operationally critical.

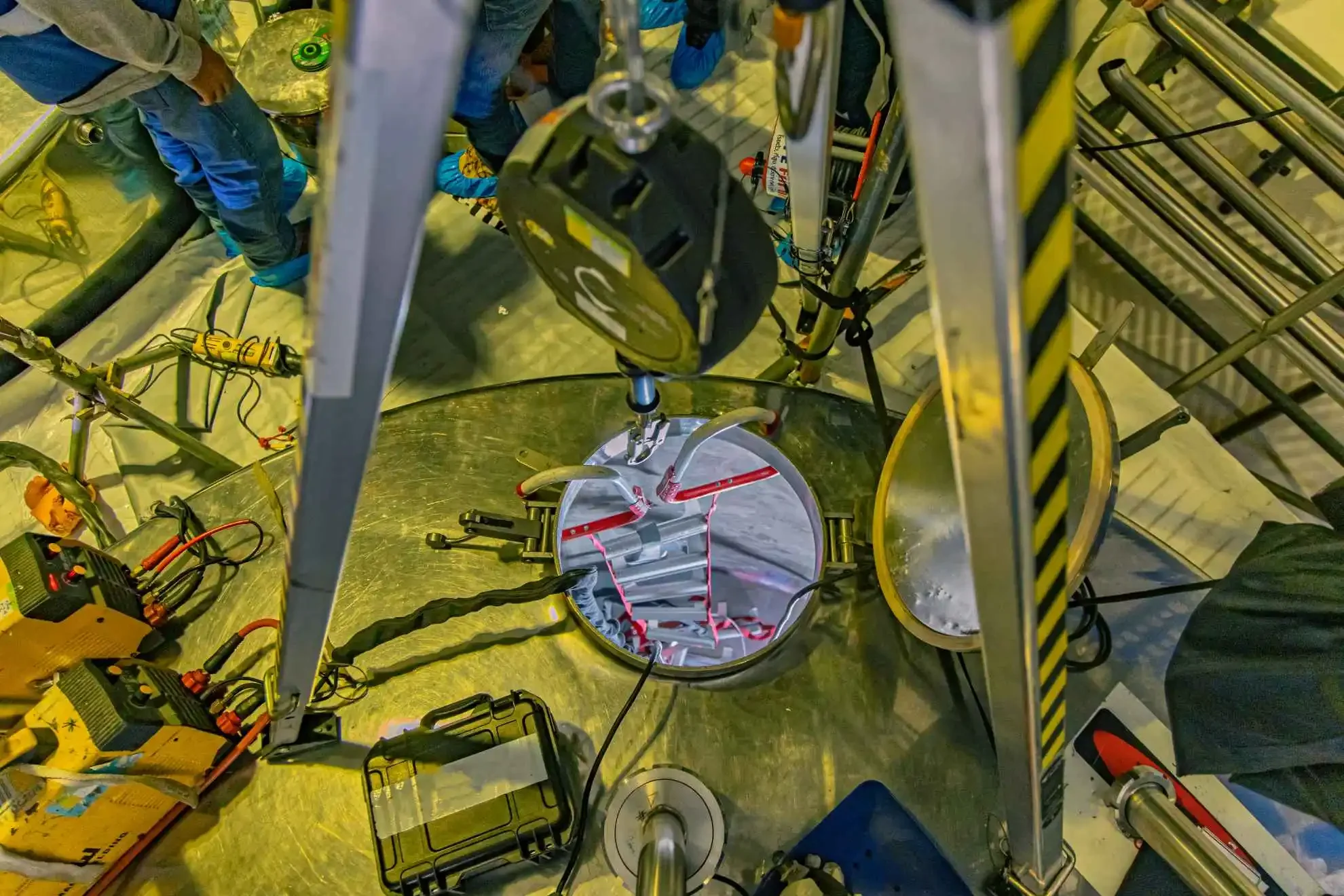

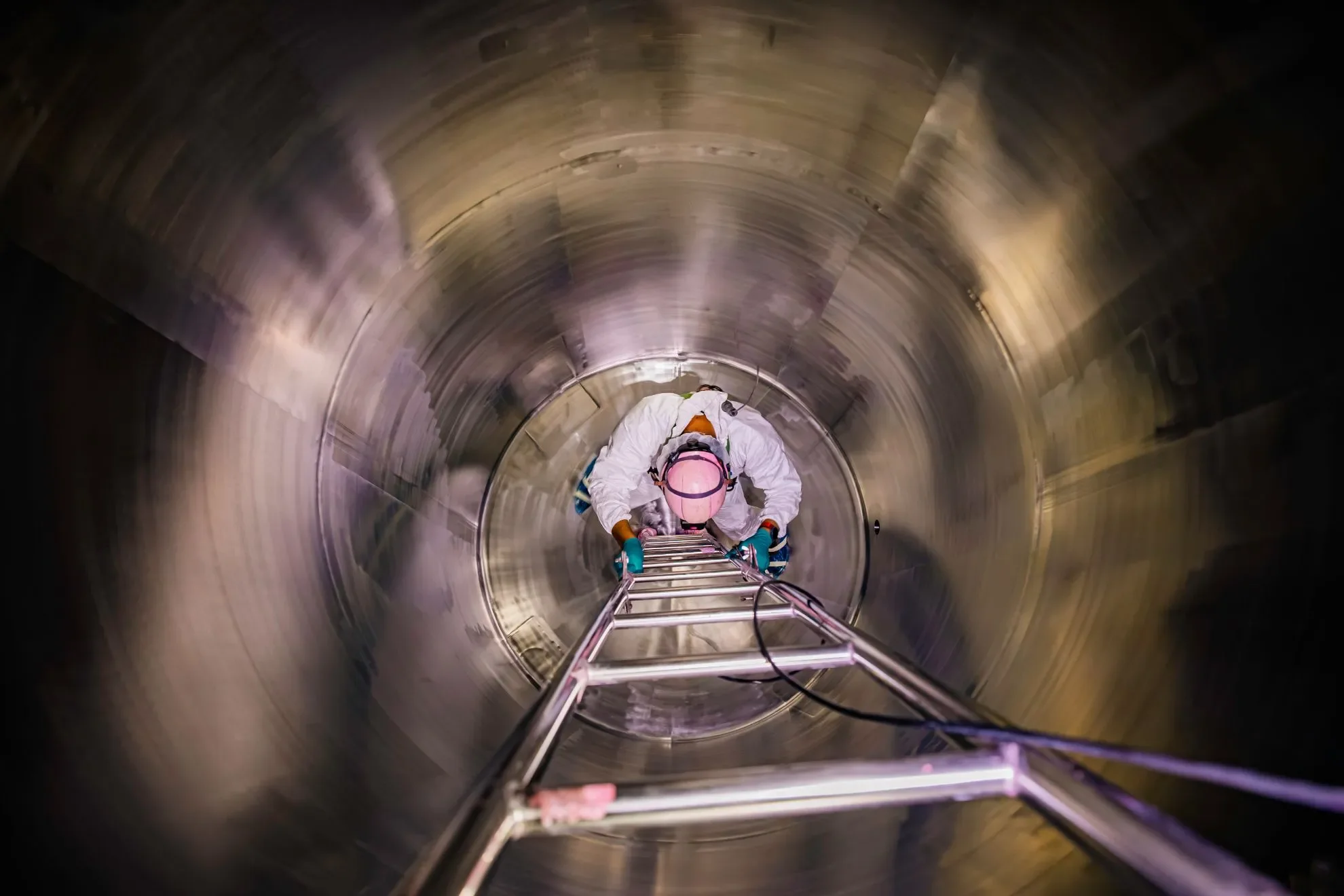

The realities of confined space rescue

Confined spaces are unforgiving environments. Access is limited. Egress is slow. Visibility is often poor. Communication can be unreliable. Everything takes longer than you want it to, even when the plan is sound.

Casualties are rarely neat or predictable. They may be hypoxic, unconscious, injured, unwell or panicking. They may have been exposed to hazardous atmospheres, extreme heat or physical exhaustion. In some cases, a collapse or traumatic event is what caused the incident in the first place.

Rescue teams are often required to work in awkward positions, in poor light, while wearing restrictive PPE. Simple actions such as reassessing a casualty, maintaining an airway or controlling bleeding become far more difficult than they would be in an open environment.

In many cases, the real challenge is not reaching the casualty. It is keeping them alive and stable while you do.

That is the reality of confined space rescue, and it is where preparation either pays off or is brutally exposed.

Why casualty care matters in confined spaces

In a confined space, you do not have the luxury of time, space or ideal positioning. Decisions have to be made under pressure, often with incomplete information and limited monitoring.

Airway compromise is common. Hypoxia develops quickly. Casualties may be trapped in positions that make assessment difficult or restrict intervention options. Extraction can be prolonged, and the physiological stress of the environment affects both the casualty and the rescuers.

Issues commonly encountered during confined space incidents include:

Loss of airway control due to reduced consciousness or positioning

Hypoxia caused by atmosphere, exertion or restricted ventilation

Collapse related to heat, fatigue or exposure

Traumatic injury during entry, movement or extraction

Underlying medical or traumatic events that triggered the incident

If a rescue team cannot assess, prioritise and manage life-threatening problems early, technical excellence alone will not save the casualty. You can execute a flawless extraction and still lose them if deterioration is not managed along the way.

This is why casualty care is not an optional extra for confined space rescue teams. It is central to the response.

Where FREC 3 fits into rescue operations

FREC 3 is not advanced clinical care, and it is important to be honest about that. It does not turn someone into a paramedic, and it does not replace higher levels of care.

What it does provide is something highly relevant to rescue environments: a structured, reliable framework for managing casualties under pressure.

For confined space rescue operators, FREC 3 develops competence in:

Systematic casualty assessment using a recognised approach

Early identification of life-threatening problems

Management of catastrophic bleeding

Airway and breathing support within scope

Clear role allocation and team working

Effective communication, escalation and handover

These are not abstract skills. They are the fundamentals of functioning effectively when conditions are hostile and time is against you.

In real rescue environments, fundamentals matter far more than obscure or rarely used interventions. Teams that can assess properly, prioritise correctly and act decisively are far better placed to manage deteriorating casualties during prolonged or complex extrications.

FREC 3 also gives teams a shared response language. When everyone understands the same approach to assessment and prioritisation, operations run more smoothly. Hesitation is reduced, decisions are clearer, and actions are more deliberate.

Those benefits are operational, not theoretical.

Decision-making under pressure

One of the least discussed benefits of appropriate training is its impact on decision-making.

In confined spaces, rescue teams are often forced to balance competing priorities: speed versus safety, intervention versus extraction, risk to the casualty versus risk to the team. Without a clear framework, those decisions become improvised.

Training gives responders a way to think clearly under pressure. It helps them identify what actually matters in the moment and avoid being distracted by non-critical issues. That clarity is invaluable when time, space and tolerance for error are all limited.

Training alone is not enough

Good training, however, only works when it sits inside a wider operational framework.

Casualty care does not exist in isolation. It has to be supported by:

Clear rescue planning

Defined emergency arrangements

Appropriate equipment

Teams who are resourced and ready to respond

For organisations responsible for confined space rescue provision, training must sit alongside proper rescue planning and response capability, not exist as a standalone tick-box exercise.

This is where many organisations fall down. Certificates are issued, boxes are ticked, but the wider system is fragile. When something goes wrong, the gap between training and reality becomes obvious very quickly.

A joined-up approach is what turns training into something operationally meaningful.

What good looks like in practice

In well-run confined space operations, the same pattern appears again and again.

Rescue teams understand the space.

They understand the risks.

They understand their role.

Casualty care is integrated into the rescue plan, not bolted on afterwards. Deterioration is anticipated, not reacted to late. Care begins early and continues throughout the rescue, rather than being deferred until extraction is complete.

When something goes wrong, teams do not improvise. They follow a plan, apply their training, and manage the casualty while the rescue unfolds. Decisions are made deliberately, not reactively.

Training such as FREC 3 plays a vital role in that system. Not because it is glamorous or cutting edge, but because it works. It gives people the tools to make good decisions in bad circumstances.

In confined space rescue, that is often what makes the difference.